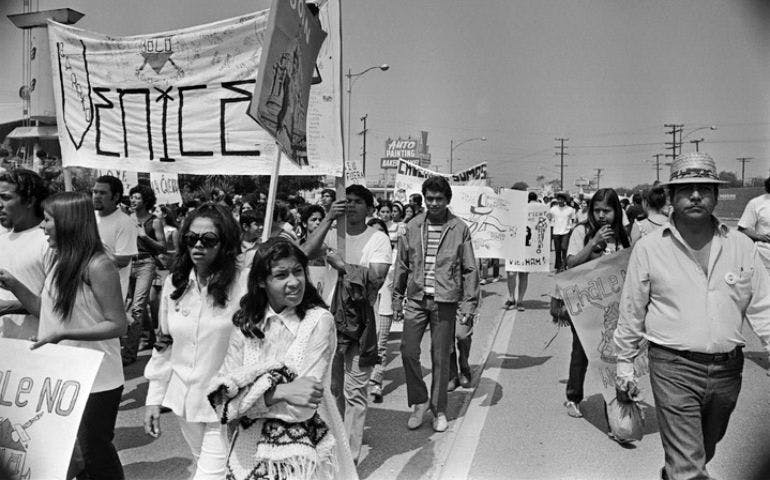

50 Years Ago –Lest We Forget

By: Herman Baca

Fifty years later, I can still vividly remember what happened to me personally and politically in Los Angeles, California on August 29, 1970.

At the time, I was 27 years old, today I’m 77.

In those 50 years, many persons I knew that marched in the Chicano Moratorium are no longer with us. In other words, “An era is slowly, but surely coming to an end.”

In 1970 unlike 2020 La Raza was a minute minority, known to U.S. institutions as the, “Forgotten, silent & invisible minority,” today we number 70 million Chicanos/Mexicanos/Latinos.

In 1970, thirty to forty thousand Chicanos from throughout the U.S. marched in the streets to protest and call for an end to the war in Vietnam. A war, like Afghanistan today, that was destroying our most precious legacy, our youth.

On August 29, 1970, a police riot ensued and Los Angeles Times Reporter Ruben Salazar, along with Angel Diaz and Lynn Ward were killed. Numerous persons were wounded and hundreds were jailed by the L.A. Police and Sheriff’s Department. Revolutionary Chicano Leader, Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales (also jailed) stated, “The disturbance (police riot) we feel was planned to disrupt the greatest, the biggest and most historic march against the war by Chicanos in the history of this nation.”

In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson had declared Vietnam a “police action.” Dark and foreboding war clouds were present in every Chicano barrio throughout the Southwest. While many young white males received college deferments, white controlled draft boards systematically drafted poor people, blacks and especially Chicanos, in record numbers to fight the war in Vietnam.

At the time, Chicanos comprised 6% of the nation’s population, but made up 20% of the wars casualties. After five years of the war, reality finally hit the Chicano community. Young Chicanos were dying in obscene number, “body bags” were being returned to the homes of grieving families throughout the U.S.

The Chicano Movement recoiled in anger and called for protests against the government’s policy of sending its young people to die in foreign wars. The movement’s political position had always been that the white racist system had made Chicanos strangers in their own land, placing them last in jobs, education and rights while placing them first to die in its wars.

GENERATIONAL DIVIDE:

In the early stages of organizing the Moratorium, a “generational” divide arose over the movement’s anti-war position within our community.

Bitter discussions and arguments occurred in our own families. Strong opposition to the anti-war position came mainly from the men we loved, admired and looked up to; our grandfathers, fathers, uncles and older brothers.

There had always been a long tradition of military service within the Chicano community. Many had proudly served with distinction (my own father included) and died in World War II and Korea. In fact, Mexican Americans are the most decorated and have won the most Medals of Honor of any ethnic group in the U.S. To the men of past generations (who had never been political), service in the military equated to “machismo.” The older generation could not understand why if we were men, we did not want to enlist or serve in Vietnam?

However, as the war and casualties wore on many of the same veterans began to understand and support our anti-war position.

At the onset, Moratorium demonstrations were planned as peaceful protests, seeking redress from the U.S. Government, based on rights supposedly protected and guaranteed under the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights.

On Saturday August 29, 1970, three individuals and I arrived in Los Angeles from San Diego around 7:00 AM. As we began to gather, I witnessed something I had never seen before; thousands upon thousands of Chicanos from all over the U.S. including many from New Mexico, Texas, Colorado, Arizona, and the Midwest all taking part in a political event.

From San Diego alone, 1,000 people attended the demonstration. The Moratorium demonstration turned out to be the largest protest organized by Chicanos in their 130 years history as a conquered people in the U.S.

THE MARCH STARTS LATE ON A HOT AUGUST DAY.

When the march started, people rallied behind banners of the Virgin de Guadalupe, MAPA, Brown Berets, MEChA, Crusade for Justice, UFW, etc. People yelled words of encouragement along the route, and many joined the procession.

After five long miles the crowd finally arrived at Laguna Park (now Salazar Park). Upon arriving, a friend and I went to get refreshments at a liquor store. When we started back into the park we noticed hundreds of sheriffs and police officers stationed across the street on Whittier Blvd., the both of us being naive thought it odd, but we did not think twice about the police presence.

Sitting down in the park, we first heard a commotion and saw police coming from the direction we had just left. Suddenly, police began to advance on the peaceful crowd without any provocation. The majority of the crowd at the front of the demonstration had absolutely no idea what was happening.

The Brown Berets (security) rushed forward and attempted to explain to the police that everything was under control. It was of no use, as the police began to beat the Brown Berets and a full-fledged police-instigated riot was under way.

As the police advanced, I witnessed scenes that I will never forget; hundreds of our people (children, women, young, and old) being beaten, tear-gassed, maimed, and arrested. The police and sheriff deputies appeared to be totally out of control and seemed to be crazed with a desire to hurt, maim and kill Chicanos.

ZOOT SUIT RIOTS REMEMBERED, SEEMED LIKE 1940 ALL OVER AGAIN!

Chicanos witnessing the attack stood up in self-defense and fought back. I remember at one point, the bright August sky turning black because of the large number of objects being thrown back at the police. People protected & defended themselves by throwing bottles, cans, sticks, dirt; any object they could get their hands on.

For a while, the crowd appeared to have the upper hand. Two or three times, they pushed the police back. However, soon the police regained control. At that moment, I learned a political lesson I have never forgotten.

Even though there were only hundreds of police and thousands of Chicanos, the police had something we lacked: organization. As I stood in the park amidst the litter, the police began lining up in formation, waiting for something to happen. I soon found out what the police were waiting for; a change in the wind direction. Suddenly, tear gas canisters were landing 3 or 4 feet from the crowd.

As the canisters hit the ground, everyone began to retreat. If you have ever smelled tear gas you would readily understand why the crowd retreated!

Most of us had no idea where we were. We started to walk with hundreds of other people down Whittier Blvd. While walking, we saw undercover police coming out from the sides of the streets, guns drawn shooting into the sky, and then at the crowd.

A Good Samaritan stopped in a truck and asked if we needed a ride. He drove us to the Mexican American Political Association headquarters (MAPA) where State President Abe Tapia and Bert Corona were going to hold a press conference to denounce the police’s actions, which they labeled a “police riot.”

Around 6:30 P.M. we finally departed to San Diego, and I remember looking back and seeing East Los Angeles burning!

After the August 29, 1970, “police riot” things were never the same for many Chicano Movement activists. Many individuals, fearful of police violence and government surveillance, left the movement and never returned. A larger number simply buckled down (today’s His-Her panic movement) to work within the system.

Others, who witnessed the events of that day, became angrier. They lost their fear, strengthened their political resolve, and continued with the struggle.

FIFTY LONG YEARS HAVE PASSED:

For many, the political question remains. Has anything really changed socially, economically or politically for our people?

Obviously one has to be an idiot to state nothing has change.

In 2020, we are no longer the, “Forgotten, silent & invisible minority,” but the largest (70 million) ethnic group in the U.S. & numerous individuals have socially, economically, and politically “made it.”

However the unfortunate truth 50 years after the Chicano Moratorium remains:

- The masses of our people have not “made it.”

- 172 year after the end of the U.S./Mexico War of 1848, Chicanos remain a conquered, colonized & powerless people, comprised of the most a-historical, a-political generation (25-38% support Trump?) in our history.

- More of our youth are in prisons than colleges; police/migra brutality, unemployment, inadequate housing, and corona virus infections, still remain.

- Babies, children jailed in detention (concertation) camps, thousands of Mexican dying yearly at the U.S./Mexico border and massive violations of our peoples’ civil/human rights are committed daily by Trump’s Gestapo… Homeland/Ice/Border Patrol in our communities.

- The political reality in 2020 is, “White Devil,” so-called President Donald Trump has declared war on Chicanos/Mexicanos/Latinos. The reason, changing demographics in the U.S. According to the U.S. Census Dept. whites will be reduced to minority status (48%) & Mexican & Latin ancestry will increase to over 33% of the U.S population by 2048.

50 YEARS LATER, THE HISTORICAL STRUGGLE CONTINUES:

As Chicanas/os gather to commemorate the historical 50th Chicano Moratorium on August 29, 2020, Chicanos will remember those who were beaten, tear-gassed, jailed & killed. Further to remind today’s generation and posterity (again) that only thru our peoples’ historical principle of self-determination will political, social, & economic power be built…to confront, address & resolve the myriad of historical problems/issues that afflict our people.

Herman Baca is a Chicano activist best known for grassroots community organizing.

He was a key figure in the Chicago Civil Rights Movement since the 1960s. His writings

and personal documents have been preserved at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD).

Arturo Castañares

Arturo Castañares